Weeds and Wildflowers

I quit my job at the beginning of the summer. If you're surprised, I was, too.

It's rare for me to make a move without planning and researching each step in advance. I especially like to rehearse all possible worst-case scenarios, so I'll be prepared when they happen. (If this sounds terrible, it's because it is. Truly just an awful way to move through life. I'm working on it.)

Also, I rarely quit things (big things, at least). I had to add that caveat because I can almost hear my mom from here, ready to shout that I quit everything she enrolled me in when I was younger, which is true. I quit small things quite easily. But I find it much more difficult (almost impossible) to call it quits on the big things, the things that shape your days and anchor your life, even if I know they've long since stopped being good for me—things like jobs or relationships.

Yet somehow, I did quit my job. I gave my notice, wrote my thank you notes, mailed my laptop back, and poof. Six years with the same company came to a close just like that.

It was astonishingly easy.

It was surprisingly hard.

The question of what to do next loomed large in my mind. After some thinking, I decided to use part of my savings to take the summer off. I felt burnt out and uninspired, and I wanted to spend time with Olive, who has taken a backseat to work more often than I'd like to admit. At 10, she's teetering on the precipice of adolescence, and I get the panicky sense that I might have just a few more years before she finds me mortifying and intolerable, and I’m determined to soak up this time wherever I can.

So, I had no real plan but I wasn’t in total freefall, either. I put out some feelers and got a few clients and projects lined up for the fall, but taking this much time off still felt inexplicably terrifying, and I struggled with the idea a lot more than I thought I would.

I've worked since I was 14 — babysitting, retail, slinging donuts at the Calgary Stampede, working for small-town newspapers, youth work, freelancing, you name it. Even on maternity leave, I was finishing the manuscript and doing final edits for my book.

I was a single parent for seven years, and I think I'd grown used to feeling like I carried the responsibility for everything on my shoulders and mine alone. Although I’m now parenting with a partner, it still seemed almost incomprehensible to envision putting some of it down, even just temporarily.

The idea of not working for a few months and, after Olive went to her dad's for the summer, not parenting either, was an unfathomable luxury, almost unspeakably indulgent. What would I do? And, more importantly, who the hell did I think I was? Why did I think I, of all people, deserved to relax for a few months? Had I really earned a privilege like this?

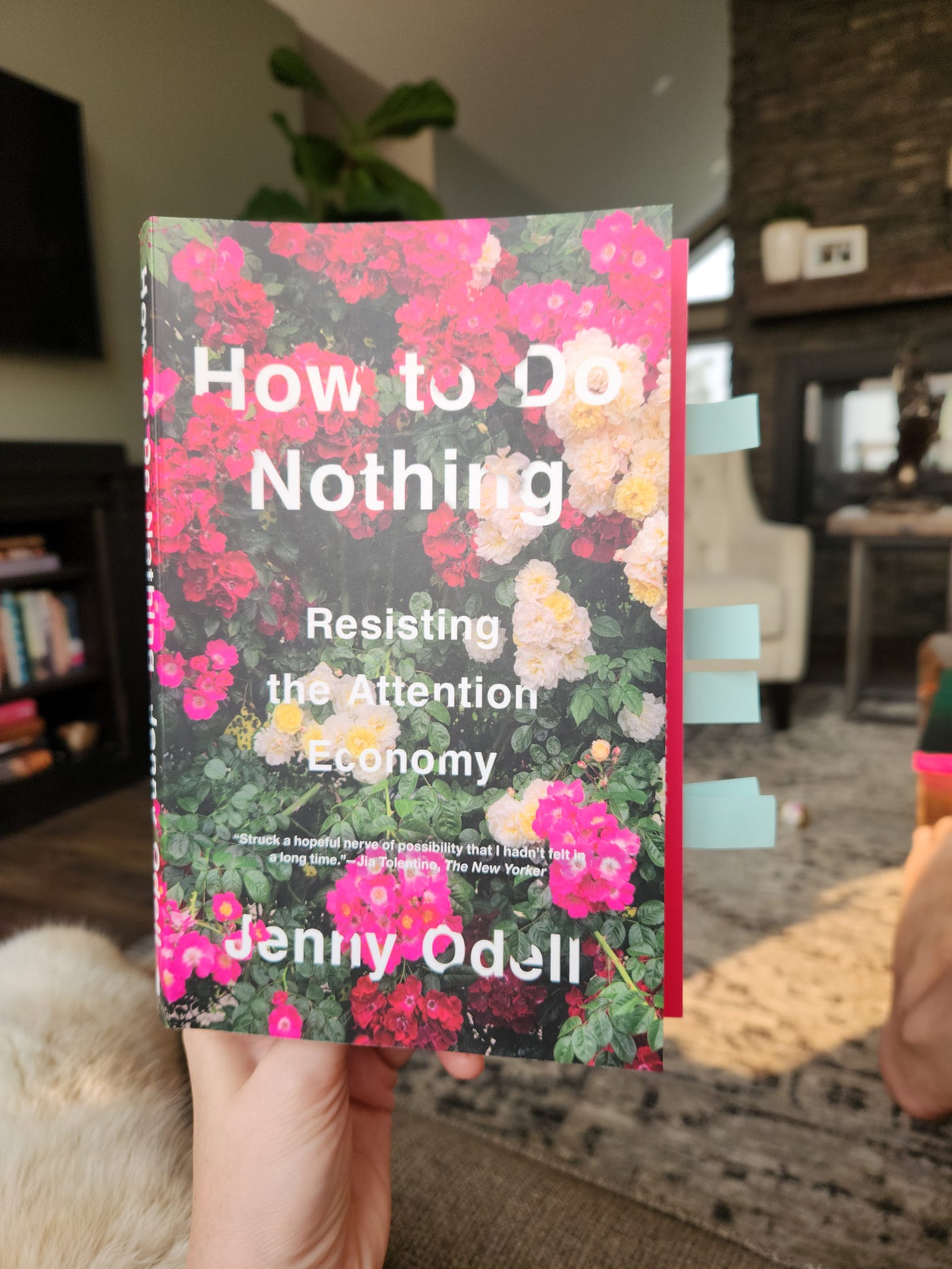

When I talked to my sister Hilary, she reminded me that rest doesn't need to be earned. She said that although we’ve been trained to equate our worth with productivity (stuffing every minute with side hustles and passive income schemes), there is innate value in simply existing as a human being. Then she recommended I read How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell.

When I spoke to my sister Mawney, she told me I needed to enjoy the summer, and I was overdue to take a break and a deep breath, and then she, too, recommended How to Do Nothing.

I ordered the book from a local bookstore and spent the next few days reading and highlighting, marking significant sections with sticky tabs and taking notes. I was absolutely determined not to waste this time. I was going to do nothing better and harder than anyone ever had before.

For the first month, I raked a lot. I have no explanation for this other than it was such an incredibly joyous shock to my system not to sit in front of a computer for eight hours a day that I just wanted to move my body and be outside. I was also very conscious about being productive, however, (having not quite learned the lessons in the book, despite my best efforts). So, after Olive left for school each morning, I would head into our backyard and spend hours raking the dead grass flattened and killed by huge snowdrifts over the winter.

Our yard is about twelve acres, so this kept me busy for quite a while. My palms grew blisters and then calluses; my arms gradually tanned. I didn't know what I was doing or why, but I knew I was doing something. And a lot of it.

(Only once did it occur to me that this might be what a mild breakdown looks like. Just a nice l'il menty b.)

Then came the wildflowers.

Being outside so much made me notice how stark our landscape is, so I ordered native wildflower seeds and spread them over a large mound covering the septic system at the back of our yard. I envisioned a lush meadow, a haven for birds and bees and butterflies. It would be a riot of colour, a wild burst of tangled beauty.

But for weeks after planting, the only thing that grew was weeds.

Eager and tenacious, they sprouted faster than I could pull them. Every few days, I'd head out with my plant identification app, hoping to see some wildflower seedlings popping up, but the results came back fast and furious with their terrible names:

Pigweed

Goosefoot

Bastardcress

Stinkweed

Devils tree

Lesser swine cress

Black medic

Prostrate knotweed

Cleavers

It was overwhelming.

I spent hours out there while Olive was in school, crouched in the dirt in my stupid straw hat, picking weeds one by one. Every so often, people would drive past on the gravel road beside our house and I felt foolish and crazy, putting in all of this work with nothing to show for it. I filled a colossal bucket every day, but the weeds were relentless and neverending. What's worse, nothing else seemed to be coming up.

I was standing in the backyard staring at my sad, scraggly weed patch one dusky June evening, feeling defeated, when Mike came out and helpfully offered to spray the whole thing with herbicide. It'll help you get rid of all the weeds, he said, but it'd kill the wildflowers, too, if there are any.

It was a tempting offer. I could cut my losses and take it back to a blank slate. Plant something else. After all, I'm good at quitting. I'm great at starting over. But I couldn’t let go of the idea — the meadow in my mind, those wild blooms that I started from seed and hoped into existence.

I also had something I haven't had in what feels like decades: Time.

What else did I have to do but pull weeds? What was more important than being there in the sun and the wind, bare feet on the warm earth, fingernails black with dirt? For the first time in six years I didn’t have any deadlines or Zoom calls, meetings or deliverables. What else should I be doing but finding weeds and pulling them, filling buckets with their limp stems and long taproots; watering in the evenings and hoping for flowers?

I abandoned the plant app, put the book's advice into action, and started to pay attention to the plants sprouting up. I began recognizing the weeds by their silvery, arrow-shaped leaves and twisted purple stems — the deceptive white flowers and the sharp smell of garlic when you crush the leaves between your fingers.

Pennycress. Lambsquarters. Flixweed. Mallow.

Pull. Pull. Pull. Pull.

It became something like a meditation. I’d be out there for hours, my mind the blank slate. I wasn't earning any money; I wasn't producing anything useful. I didn't know what I was doing or why, but I was doing a lot of it. And I loved it.

Over time, the weeds became fewer and fewer, and, in their own time, the wildflowers began to emerge. Their names were bright and pretty: Poppies, Cornflower, Sweet Alyssum, and Tidytips. Zinnia, Baby's Breath, Scarlet Phlox, and Scarlet Flax. Yarrow, Lupine, Purple Tansy, and Wild Chamomile.

Not quite a riot but a low rumble. Not yet a wild burst, but certainly the start of something beautiful.

There's an overwrought metaphor in here somewhere about hard work and tenacity; productivity and paying attention. About working through the weeds until you see the wildflowers and how hard it can be to tell the difference sometimes.

There's a lot I could say about the things I've held onto too long for fear of starting over and how I've learned to love the work that goes into growing something great — work that feels good, like sunkissed skin and warm earth, new blooms every day.

I've decided that it's high time I did start writing about these things again, especially since I now have the time. Life and love and parenting and this quiet adventure of living on a farm surrounded by wheat fields. I've really missed the practice of looking around my life and then laying my thoughts on a page; arranging my world in words.

If you’d like to join me in this new conversation, you can subscribe to this Substack. Posts get delivered to your inbox, but you can also read them here on the site and leave comments. There's no pressure to subscribe, and if you're unsure whether you'll like it, you can always try it for a month and cancel if it's not your thing. (We're allowed to quit something that isn't working for us, after all.) And if you have financial constraints, please email me and I’ll gift you a subscription — there’s room for everyone here!

I've called my substack "The Rigmarole" because it's an objectively fantastic word that's fun to say and also because it means "a long, rambling story or statement," which somehow feels appropriate for the way I write.

I'll be sending out a new post every week — mostly wildflowers, but maybe the odd weed, too.

I've missed you and I hope you’ll join me here. Together, we can grow something beautiful.

Madeleine

This inaugural post was meant to be sent to grandaddy - I don't know why but it is him all over. Welcome back!

Proud of you for leaving something that didn’t serve you and excited to read more!